In the quiet hum of Frankfurt’s financial district, where the European Central Bank’s glass tower looms, a pivotal decision is brewing. On Thursday, the ECB is all but certain to cut its benchmark interest rate, now at 2.25%, by a quarter point, following May’s inflation dip to 1.9%—below the bank’s 2% target. For families like Sofia Mendes, a Lisbon baker juggling rising costs, the move promises relief through cheaper loans. But as ECB President Christine Lagarde prepares to announce the cut, Europe faces a tangle of hopes and risks, from revived growth to the looming shadow of U.S. tariffs.

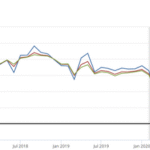

The rate cut, signaled by Lagarde’s recent comments on “easing restrictive policy,” responds to cooling inflation, driven by falling energy prices after a 2021–23 surge that hit 10.6%. The ECB’s goal is to spur borrowing and investment in a eurozone economy projected to grow just 0.9% in 2025, down from 1.3%, per the European Commission. “Lower rates mean I might finally afford to expand my shop,” said Mendes, her hands dusted with flour as she shaped dough. The cut will lower borrowing costs for mortgages, car loans, and business investments, potentially boosting consumer spending. ECB models suggest a 0.25% cut could add 0.2% to GDP over two years.

Yet, the move isn’t a cure-all. “We’re in a delicate spot,” said Pieter van der Meer, a Dutch economist, noting the eurozone’s vulnerability to external shocks. U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariffs—25% on EU steel and autos, with a proposed 20% levy on all goods—threaten to crimp exports, which drive 7% of the bloc’s GDP. Recent Paris talks between EU negotiator Maroš Šefčovič and U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer yielded no deal, with a July 14 deadline looming. “If tariffs hit, any growth from rate cuts could vanish,” van der Meer warned. The EU is readying countermeasures, like duties on U.S. whiskey, which could raise prices for consumers.

Lagarde faces a balancing act. “We’ll proceed cautiously, watching trade and geopolitics,” she said last week, hinting at further cuts if inflation stays low. The ECB’s deposit rate, a key driver for bank lending, is expected to hit 1.5% by mid-2026, per analysts at ING Bank. But risks abound. A weaker euro, down 2% against the dollar since April, could stoke import costs, nudging inflation up. China’s rare earth export curbs, hitting auto suppliers like Germany’s Thyssenkrupp, add supply chain woes, potentially offsetting rate cut benefits. “My car parts are getting pricier,” said Luca Rossi, a Turin mechanic, fearing higher costs for customers.

The context is complex. The ECB’s last cut in March 2025 sparked a brief stock market rally, but gains faded as tariff fears grew. Europe’s industries, from Nissan’s struggling plants to Stellantis’ tariff-hit factories, face pressure, with job cuts looming. Yet, lower rates could ease burdens for small businesses and households. “A cheaper mortgage would help us breathe,” said Anna Kowalski, a Warsaw nurse with a young family. Economists like France’s Agnès Bénassy-Quéré see a “window of opportunity” for growth if trade tensions ease, but warn of stagnation if talks falter.

Reactions are cautiously hopeful. “Lower rates are great, but tariffs could ruin it,” said Hans Weber, a Munich factory worker. Industry groups like CLEPA urge the EU to secure supply chains, while firms like Phoenix Tailings in the U.S. eye rare earth recycling to fill gaps. Bankers expect a lending boom, with Germany’s Commerzbank forecasting a 15% rise in small-business loans by 2026.

The implications are high-stakes. Rate cuts could fuel housing markets and consumer spending, but a trade war risks price hikes and job losses. The ECB’s next moves hinge on inflation data and U.S.-EU talks, with a Trump-Xi Jinping call this week potentially easing China’s curbs. Questions linger: Can rate cuts outpace tariff damage? Will Europe’s economy rebound or stall? For now, as Mendes kneads dough in Lisbon and workers watch factory lines, the ECB’s cut offers a glimmer of hope, but the shadow of global trade looms large.